On 14 September 2021, MB&F presented the latest version of the Legacy Machine Perpetual, with the famous perpetual calendar movement designed by Stephen McDonnell. It is a 25-piece edition in palladium, a metal more expensive than gold and very hard to craft. The watch is in verdeaux (grey-blue) colour, with the same pushers previously seen on the Legacy Machine Perpetual EVO. The LM Perpetual is a remarkable chapter in the dazzling world of MB&F, one of the top three best sellers, winner of the GPHG prize in 2016, and the movement, which is totally different to anything seen before for this complication, is pivotal in determining the design’s success. So we were delighted to be able to talk to Stephen McDonnell, who is based in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and ask him about what sets the Legacy Machine Perpetual apart from all other perpetual calendar watches.

Stephen McDonnell, watch designer and constructor

“The perpetual calendar has been around for about 150 years, but there are many things about the conventional configuration of the perpetual calendar that are really weak and can be improved. In designing watches, my standpoint is usually, how can we make this as good as possible, setting aside all the conventional wisdom, starting from a blank piece of paper and imagining that this is the very first time that there has ever been a perpetual calendar?

“The first thing that I wanted for this mechanism was that it had to be really reliable. Max (Maximilian Büsser, founder of MB&F) had worked previously with some other high-end watch brands, and he’d had nightmares with perpetual calendar watches. Max called them boomerang watches, they kept coming back! Usually in a perpetual calendar watch there is a two-hour window between 11.30 pm and 1.30 am when everything is happening, and if the customer starts messing about with the correctors at that time, turning back the hands, or pressing the correctors while turning the hands – people can do daft things – you can break the tips off the teeth, and once you’ve damaged it, it’s game over, it has to go back to Switzerland for repair. So the first thing that we felt essential was to make a watch that was completely fool proof. MB&F tests all the LM Perpetual watches that they make, they play with them and try to break them, and there’s nothing you can do to them to make it go wrong. It’s got so many safety features.

The date subdial on a conventional perpetual calendar watch (the inner ring shows power reserve)

“There’s another thing that really bothered me with conventional perpetual calendar watches. When you look at the date ring, with the numbers from 1 to 31, it always goes 1 dot 3 dot 5 dot, right through to 27 dot 29 dot 31, and then 1, without the dot between 31 and 1. So when you look at the date ring, at the top you see 311! It’s terrible! That’s something that annoyed me for years and years, and I thought, there should be a dot between those two numbers 31 and 1. But there’s no way you can fit that dot in with a conventional mechanism, because it would effectively correspond to an extra day.

“Something else that I wanted to do better was the precision of the display. A conventional mechanism is based on a wheel with 31 teeth, because 31 is the longest possible month. So if you observe what’s happening around midnight on 28th February, what you’ll see is that the watch will go to 29th February, sit on the 29th for half an hour, then it will move to the 30th, stay there for half an hour, then 31st February and sit on that for half an hour, and then at last it will go to 1st March. So it cycles through three days in a two-hour period, and in that period you have these anomalous readings, and I find that very untidy. I wanted a watch that could go instantaneously from 28th February to 1st March, with nothing in between. That’s why I had this idea for the new system which is more reliable, and which would enable me to put a dot between 31 and 1 to make everything neat. And I could move directly from the last day of the month to the first day of the new month without any messing about.

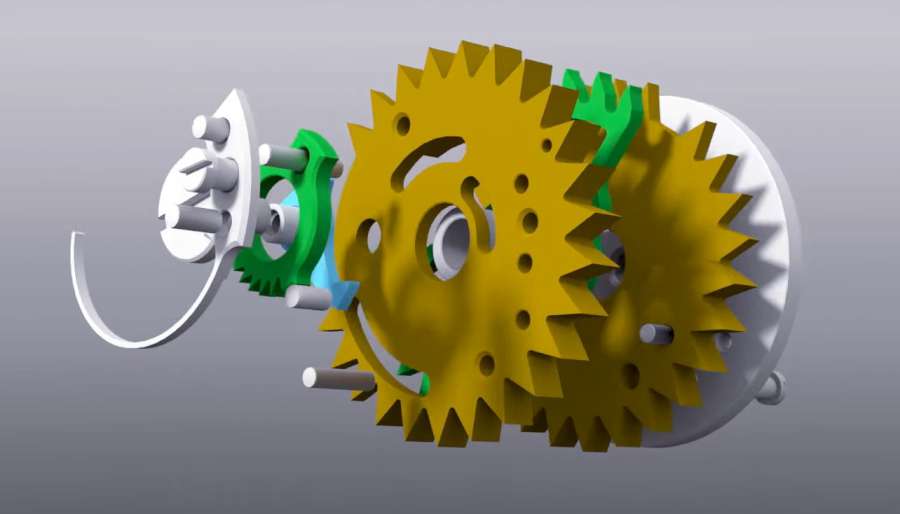

“I had the basic idea in my head when I first talked to Max. What I thought was, rather than having a wheel with 31 teeth, I’ll base the calendar on a wheel with 28 teeth, because 28 is the shortest possible month, and then add in the extra days whenever I need them. This is achieved by a multi-stacked mechanical processor, a wheel with five levels. The watch programmes itself on the 25th of every month. The programming system moves a disc with a sector for the correct number of teeth to be added. So for each month, there is always exactly the right number of days: the display goes instantaneously from the last day of the old month to the first day of the new month without any messing about.

“The other advantage that I should mention is that the system allows you to directly correct the year. A perpetual calendar has a four-year cycle. In a conventional perpetual calendar, you have no access to the year. You only have access to the months corrector. So if you want to go back one month in the cycle, you have to go forward 47 months to get there, and that is very inconvenient. With my watch, you can correct the year directly. One press on the year corrector at 8 o’clock enables you to move forward by one full year in the cycle, which is another big advantage.”

And is it easy to adjust for the leap century, the adjustment that has to be made once every hundred years?

“Yes, the watch doesn’t calculate for the leap century, but because you have direct access to the years, it takes just four presses of the button to correct for that, it’s extremely straightforward”.

One of the most stunning features of the LM Perpetual is that you can see a lot of the mechanism dial-side, not just the large balance that had already been a hallmark of other MB&F watches like the LM 101. Was that an important concept for you?

“Yes, definitely. When I look at watches, I want to see what’s going on inside, I don’t want to see just a dial and some hands ticking round and giving me some information. This was the third Legacy Machine watch, they’d already done LM 1 and 2, and both of those watches have a big bridge on the front which covers all the mechanism and creates a very clean and elegant look. So when I designed the perpetual calendar, I said to Max, I’m so excited about this mechanism, we have to show it. We discussed it, and I proposed floating dials which offer the maximum visibility for the mechanism, so that when you are wearing the watch and live with it, you can see what’s going on. For me, the ideal watch would have no dial, no hands, and it would work perfectly, it would know the time exactly, the date exactly, it just wouldn’t bother telling you what they are!”

The LM Perpetual is very symmetrical, with the leap year indicator on one side mirrored by the power reserve indicator on the other side. Is symmetry an important design element for you?

“I’m very interested in symmetry, because it brings a sort of beauty and elegance. It nurtures serenity, it makes me feel less anxious. But you can’t have everything totally symmetrical, so in this piece there is an overall symmetry, but when you look more closely at the mechanism, you see that it is not symmetrical at all. It’s the same on the movement side: there is a symmetry in how the bridges are laid out, but there are also elements where there is no symmetry at all. But symmetry makes me smile!”

Are you surprised that this very complicated design has become one of MB&F’s best sellers?

“The watch grew, like a plant, from the initial concept. We had no idea of what it would become, we didn’t know what it would look like and how many parts it would have. But perhaps people get a sense of the inspiration, of everything that went into the watch. When I’m designing something new, in my head it feels like the part already exists, as if the part were in a jar of sand, buried so that I can’t see it. As I get close to it, it’s as if I were pouring the sand away and the part starts to emerge, and when the sand’s all gone and you can see the part, I see that it’s exactly what I was looking for, and I think, of course, it could only ever look like that. And whenever I design something and get it right and it works and I’m pleased with it, there is this amazing gut feeling, and I’m always looking for this kick in every part of a watch that I design. And I think, if I work hard and ensure that I get that feeling for every part of the watch, when it is complete, other people will appreciate it as well”.

You are often described as a self-taught watchmaker. Could you give us an idea of your background and how you began watchmaking?

“I’m from Belfast in Northern Ireland, and from an early age I had always been obsessed about everything mechanical, and I was always interested in clocks and watches. But there is no watchmaking industry in Belfast, there are watch shops, of course, but culturally, watchmaking doesn’t exist here. So I always imagined that I would keep watchmaking as my private interest, I would never thought it could be a career option. So when I went through school and studied Theology at Oxford University, it remained just that, a personal interest. All my friends at university went on to do other things, like venture capital analysts and merchant bankers, but I came back to Belfast and started repairing clocks for jewellers’ shops and antique dealers. Later I found out about the Wostep watchmaking school in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, and I thought, that sounds interesting. I applied and I got in, and I went up to Switzerland in January 2001. The Wostep 20-week refresher course was my first formal training of any kind in watchmaking. I thought that I would return to Belfast and continue repairing clocks, but in actual fact the people at Wostep asked me to become an instructor at the school. So I did that and remained at Wostep for about six and a half years. After that I stayed in Switzerland and worked independently for various brands”.

Stephen McDonnell, watchmaker

So, while you were already proficient in the practical part of watchmaking, Wostep introduced you to movement design?

“Yes, that’s right. Watchmaking is in two parts. There’s the practical part, which is watchmaking at the bench, with all the machinery, making all the parts and putting it all together, and then there is the more theoretical design part, which you can learn at university in Neuchâtel where you study watch construction, which means all the technical side, the mathematics and the CAD, designing all the parts on the computer. But these two areas never really meet. On one hand you have these guys who do the design, but they’ve never sat at the bench, and on the other you have the watchmakers who can put the parts together, but they don’t have the skills to operate as designers. So generally, these two areas are very separate. I suppose that if I have any strength, it’s the fact that my background has always been in practical watchmaking, making parts at the bench and physically working with watches and clocks. After I became independent, I moved more and more towards designing watches. In the area of design, I am completely self-taught, I’ve never been to any sort of school or college for that, but the fact that I have the practical watchmaking background means that whenever I design stuff on the computer, I see through the eyes of the watchmaker and that gives me a useful insight as to how it’s all going to work later on”.

For a watch like the LM Perpetual, did you design all those specific parts yourself, or were you working with a team of watch designers and watchmakers?

“For the LM Perpetual, I designed everything from scratch, starting from the concept, right through to designing the parts using CAD so that they could then be made by MB&F’s suppliers. I built the prototype, I always build the first prototype and get the watch to work, because even with the best computer modelling, there are a lot of things that you just cannot be sure about. It all looks fine on the screen, but you can’t make it run dynamically, you can’t get the watch to function. In a watch like a perpetual calendar, you often have moments when things are moving very fast, and particularly with calendars, this is a problem. The computer can’t really model the inertia of the parts and how they accelerate, how they impact and rebound. Whenever you make these things work in real life, the results can be very surprising. Of course, if you’re working with something that is totally conventional, you can design it 99% on the computer and it will work, but when you are designing things that are fundamentally new, you have to build the prototype and then tweak all the parts to get it to work properly. So I always build the prototype first, myself. But if I had to make all the parts from scratch, it would take me about five years, because, using the perpetual calendar as an example, it has about 580 components. So MB&F’s suppliers make about 80% of the parts, but I make the most risky bits of the mechanism, the ones that I know will be very problematic, here in my workshop. That means that as I make the prototype, I can test everything and see whether a spring needs to be stronger or whatever, and remake the part myself. As I work through the prototype and get everything to function, I supply MB&F with a complete dossier with everything optimized, so that whenever they put it together, it will work first time”.

How did you come into contact with MB&F?

“When I became independent in 2007, I already knew some people in the Swiss watchmaking industry, which is really quite a small community. I already knew Peter Speake, and he was one of my clients, I started making parts and assemblies for him. He was involved in the very first MB&F watch, Horological Machine 1, and was one of the friends who contributed to that project. For that first watch, Max was having some problems, because the suppliers he was working with at that time would supply the kits of parts but they weren’t willing to assemble them. He spoke to Peter, and Peter phoned me and two or three other watchmakers he knew, to see if he could get us together to actually build the new watch and produce it. That’s when I met Max: I was involved in building the prototype and getting it to work. Max and I got on well, and I think that we always felt that we would like to collaborate at some point, and when years later the opportunity arose for the perpetual calendar, they were looking for someone who could design the watch and make something interesting. At that moment I had been let down by another client and I needed to find a new project, so we happened to be in touch at just the right time. I’d had this idea in my head for ages about a new, totally different concept for the perpetual calendar, but I had no idea whether it would work, it was just a concept. So I proposed it to MB&F in 2012: they liked the idea, so we went ahead and developed it. You know the rest!”

Are there any historical watchmakers who inspire you?

“I’m a big fan of Abraham-Louis Breguet, obviously. I’m really interested in how things are made. Just consider how hard it is today to make one watch, designing all the parts, getting them made, putting them all together and getting the watch to function, it’s very difficult to do. It’s hard enough to do it with computers and computer-aided design. But thinking of Breguet, working in an era in which there was no electricity, no computers, no electric light, and still succeeding to build a watch, it’s mind-blowing. I love the way he managed to create the incredible variety of watches that he made. Admittedly he wasn’t on his own, he had a whole house behind him. But he came up with a whole variety of clocks and watches with incredible ingenuity and clever mechanical devices and innovations, and he managed to make so many – he was so productive in his lifetime.

“But my interest is across all sorts of engineering, I’m equally inspired by people like Reginald Mitchell who designed the Spitfire. A complicated watch has got maybe 600 components, but a Spitfire has thousands and thousands of complicated components, and they are all made in different factories all over the place, and every time you make a tiny change, you have to physically sit and redraw everything on the drawing board. The amount of work involved in doing that is totally incredible. I feel the same way about Thomas Andrews, the chief designer of the Titanic who went down with the ship, which was built in Belfast. He had such a vast vision of something so hugely complicated, and actually produced it in a relatively short amount of time. To me that’s mind-boggling”.

Did the restoration of clocks give you any insights and ideas?

“I spent a lot of time doing restoration in Switzerland, and I think that it’s a brilliant way to hone your skills, particularly if you want to take watchmaking to the next level. In restoration, you encounter watches with bits missing, and at first you don’t even understand how the mechanism works, you have to piece it back together from the clues on the mainplate, where the holes were drilled, where the screws went. You have to think the mechanism through properly in order to reconstruct the missing parts. So for me, restoration was an enormously important part of my training, it’s part of the experience that enabled me to work in the way that I work today.

But to answer your question about insights and innovations, that doesn’t come from restoration. Regarding the concepts for new mechanisms, my head’s full of ideas and stuff, and I have no idea where that comes from. I’m profoundly interested in mechanics, and not just watches specifically. I don’t even wear a watch, I don’t collect watches, I really like watches but my interest is all about the mechanics, what’s inside the watch. In the same way I was never particularly interested in what cars looked like: I just wanted to know what was inside the gearbox. It’s all about the mechanics!”

Read more about the LM Perpetual by Stephen McDonnell on the MB&F website.

Pingback: Watch Review: MB&F Legacy Machine Perpetual LM3 - Watch Link Blog